Valerie Bolling, Jack Wong, Lucy Ruth Cummins and Emily Joof kicked off summer by sharing four picture books about swimming; revealing the story behind their stories, and have a conversation about representing diversity in picture books.

If you missed the live session, you can watch it or read a full transcript below.

Please note: closed captions are being added to the video below. When they are finished, you can see them by hovering over the bottom of the video and choosing the “CC” icon.

Full Transcript

Alex Villasante:

Hello, everyone, welcome. I hope you are all safe and sound and well where you are. My name is Alex Villasante. I am the Program Manager at the Highlights Foundation. I’m coming to you from southeast Pennsylvania, on the traditional and contemporary lands of the Lenni Lenape people.

Welcome to our free HFGather Here Comes Summer: Reading, Swimming, and Gathering. I’m so excited about this conversation where we get to jump into summer with hearts full of joy, with family to connect with. I didn’t even mention this, but food to eat, and with wonderful books all about that summertime vibe before I turn things over to Valerie, Jack, Emily, and Lucy. I want to quickly touch on a few notes. Closed captioning is enabled for this webinar, and will also be included in the recording of tonight’s event. All registrants will get a link to that recording.

This is a webinar. We unfortunately can’t see your video or hear your audio, but we can see you in the chat and in the Q&A feature–feel free to drop a comment, a high 5, a eureka moment, where you’re coming in from, in the chat. But please place questions in the Q&A box–that way, your question won’t get lost in the chat when it is time to open up for Q&A.

In the chat, in the Zoom, in all of the spaces where we gather with the Highlights Foundation, we ask that you are respectful in your engagement with us, and that you join us with no hate, no harm, and no harassment of any kind. I’m going to see if I can do two things at once. It’s always hard but I’m going to drop a link in the chat which is a link to our community standards for those of you who are a little new to the Highlights Foundation, or for those of you who wish to read a little further about our commitment to creating safe and inclusive spaces. So let me just pop that into the chat to everyone.

Yeah, yeah, I did it. Okay. So now, enough of all that. Good stuff! I’m gonna kick it off, this, this summertime celebration by passing it over to educator, faculty member, picture book author, all-around awesome person, Valerie Bolling, who I have been at Summer Camp with. Is it 3, 3 times that?

Valerie Bolling:

It’s, it’s been 2. And this year it’s black voices. So.

Alex Villasante:

And I want you back.

Valerie Bolling:

I want to come back.

Alex Villasante:

You are…so you are summertime. You are Summer Camp material. So please, Valerie, introduce us to this summertime fun.

Valerie Bolling:

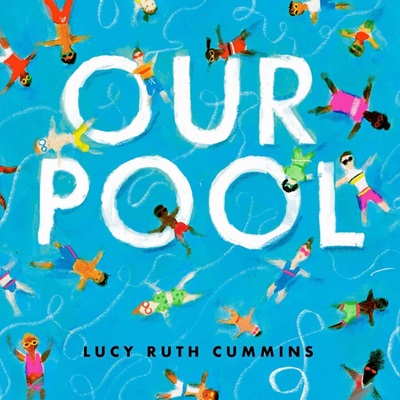

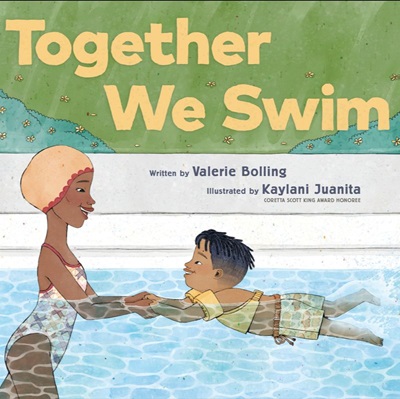

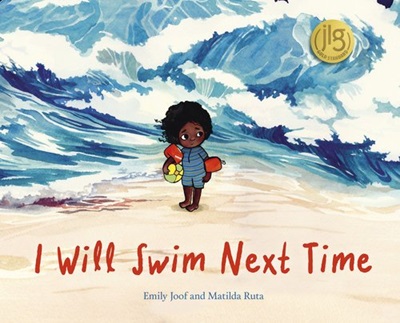

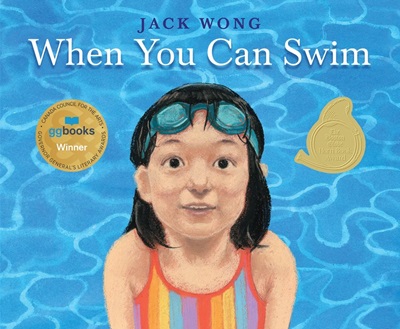

Sure. So first of all, I want to point out for those of you who may not know that May is National Swim Safety Month. So not only are we gearing up for summer, but it’s the perfect time to have a Gather about swimming and about our picture books that are all about swimming. And I wanna just, I’m not going to spend a lot of time introducing myself and my other friends here because I want us to be able to have a conversation and have enough time for you to ask questions. So Alex is going to be kind enough to drop the links to our websites in the chat, so you can find out more about us. But I thought it might be interesting for you to see how this idea came together. When my book Together We Swim–and each of us will hold up our books–when you know, when we’re talking. When my book came out last August I noticed that there were other swimming books that were already out: Jack’s book, and Lucy’s book, and then later, and also, I believe in August, if I’m correct, Emily, Emily had a swimming book come out.

And so I thought that I wanted to connect with these other creators who had all written books about swimming, and then, when I heard that, you know, Highlights does Gathers, I thought it would just be fun for us to connect and get together and talk about our books. And so that’s what we’re going to do together. And two–Jack and Lucy are actually author illustrators which is really exciting. And Emily and I, right, have just written the words, I shouldn’t say “just.” We are authors, and we’ve been fortunate to be paired with amazing illustrators.

So to start off, I’d like each of us to share just; I know it’s a typical question, but I do think people want to know where the idea for our particular books came from, you know, in other words, the story behind the story, and also, if there is maybe your own swimming story that you want to share, particularly if there’s a connection between that and your book. So I’m going to start with you, Lucy. And you can hold up your book as well.

Lucy Ruth Cummins:

Hi! So my name is Lucy Ruth Cummins, and I’m an author and illustrator, and my swimming book is Our Pool, which came out in May 2023. Our Pool is about my neighborhood pool. I live in Brooklyn, New York. I’m in the courtyard outside my apartment building, because if you live in an apartment with a 8 and a half year old and a 2 and a half year old, there’s no quiet place.

So this book is about our our community swimming pool in my neighborhood in Green Point, Brooklyn, and the reason I came to make it was, I have had a career as an art director in picture books for 22 years. And so when I, when I have an idea, my ideas always channel their way into books. It’s the way, I think. And so I was at the swimming pool with my then, probably 3 or 4 year old son and I was kind of looking around. And my artist, I kind of noticed all the interesting things that were happening around the water and all the different people who were there, and it immediately felt like a book.

And so I started making notes and started coming up with this concept for this particular book. And so over the course of 2 and a half-ish years. I developed this book and the story about our neighborhood pool.

Valerie Bolling:

Thank you. And obviously, you also, you know, have a swimming story. So there’s the story behind that. But there’s also the fact that you’re a swimmer, that you enjoy the neighborhood pool. You go there with your family, and so I often talk about, you know, especially when we you know, or speaking to children, they often want to know where do ideas come from? And I often say ideas can come from anywhere, and they are often just we find them just in our setting, just by looking around in our environment. And clearly, that’s what you did. So thank you for sharing that. What about you, Jack? And so do hold up your book.

Jack Wong:

So this is my book When You Can Swim. And what Lucy was saying and what you were saying just now, both parts of it were really interesting. Because this book was 100% inspired by just being in the environment, that it’s about which is swimming in nature. But, unlike Lucy’s book. I actually had the opposite experience of of knowing that it was a story that I would write about right away. Instead, I was…so I, I’m someone who is an adequate swimmer, not a very confident swimmer, but I have friends and family who love swimming out in nature. Be that at the pool, I mean not sorry, not the pool at the lake, or at the beach, or in the river, and I would often be part of these, you know, outings, hiking and and camping, but I wouldn’t be the most avid swimmer. So a lot of the times I spend time actually out of the water, and sketching and writing little poems, or jotting down little notes about my environment, which is something I do anyway, as an author/illustrator.

And at a certain point, when I was looking at my sketchbook or my notebook, I started to realize I had all these things about swimming, and it had been months and months before that I had been collecting this stuff over one particular summer. Actually, so it, I actually, it took me a very long time to realize that I had been working on this book unwittingly, and by the time I realized that I had most of the scenes and a lot of the words to go along with it as well.

Valerie Bolling:

Wow! That is just incredible. And that, again, is another writing tip and illustration tip: to just keep your notebook right as ideas come to you. You jot them in sometimes you may even forget about them, but when you take time to look at what you’ve jotted, whether they’re words or illustrations. You never know what you might find there. And so the idea that you had really a book that was in those notes is just just incredible. Thank you for sharing that. Emily?

You’re muted, Emily, I think. Yes.

Is it just me? Is anyone else having difficulty hearing Emily.

Emily Joof:

Here, you can’t hear me. Okay.

Valerie Bolling:

So I can hear you. I can hear you now, Emily.

Emily Joof:

Sorry about that. So I was saying that I wrote I Will Swim Next Time over a number of years. I myself can barely swim, which is, which may be a little odd. I grew up in The Gambia West Africa, right by the beach, but I never learned to swim. I’ve always had this kind of healthy distance to the water, where I appreciate it, love being in it, but don’t know how to navitage it. But then, when I became a mom, I took my own little one to the beach, and she stood there and refused to go in, and no matter how much I coaxed, and I asked, “Well, what what is it about the water?” And she said, “It just feels so loud.”

And, and I feel like, she finally articulated what perhaps I had been feeling without really understanding. Gambia has these massive, crashing waves. So it is actually, very, very loud, and in that moment I made the decision that she would be different from me, that she would meet the water in different ways. And we would hopefully allow them to get better acquainted. So, even though we visited to th,e the Gambia, we actually lived in Sweden at the time where we’re very fortunate to have a lot of quiet lakes, beaches, community pools. So over a series of years, we visited various waters, and without knowing the story, was writing itself in my head, and I think she was about 5 or 6 one day where we were sitting at an AirBnB that had a massive pool, and she just jumped right in, and I almost lost my, lost my breath.

But she just swam and as she popped back up she said, “Well, it feels just right.” And, and that was when I knew the story was set so, so that she is very much my inspiration for the story. But in a way she’s a strong reflection of my own experiences with the water. I have since taken a swim class where I was heavily pregnant with my second child, determined to do better. But I’m still kind of holding onto the edge most of the time in the pool. That’s as as good as I can I can do for now.

Valerie Bolling:

Wow! What a story! But the fact that, you know, I think it’s so important for parents not to put their fears upon their child right upon their children. So the fact that you said, you know I may not have the best relationship with water myself, but I don’t want that for my daughter. I want my daughter to swim. I want my second child to swim, and you know what I will try as well. You may never compete in the Olympics. Right, you, but the fact that you are show an example to show I can go into the water as well, and I think it’s a perfect example of the fact that we can learn at any age. You can learn anything at any age.

My husband as well grew up in Trinidad, never learned how to swim and he took swimming lessons as an adult. Is he a great swimmer or confident swimmer? No, but at least he can feel safe around water, and I think that’s one of the messages I know I give. I don’t know if you all do, too, when I share my book with children. As I say, I want you to be safe. I want you to be safe around water, and that’s why I want you to learn how to swim, and again back to May is National Water Safety Month. Last Saturday, May 18, was National Learn to Swim Day, so I think our books really do, even though we tell stories differently. There’s clearly a, a connection. I’m going to very quickly tell the inspiration behind my story, and then I want to talk about the community in each of our books.

My story is not at all exciting one. I felt pushed to write this book. I had a 2 book deal together. We Ride was the first book. It was called Bike Ride initially, and I knew that the publisher wanted a second book, and so I had come up with an ice skating book, and I was told, oh, that might be regional! And then I changed it to roller skating. I didn’t have to change much. They weren’t interested in that. And someone said, but you know the publishing director thinks a book about swimming would be great, and I wasn’t initially excited about the idea, though as a kid you couldn’t get me out of water. I did take swim lessons at the Y, I did go to camp every summer. So I was a very confident swimmer. I don’t swim now so much if I go into a pool. I, I like Jacuzzi’s and I will, I like water aerobics, so I’ll do that. But I’m, you know, I’m comfortable around the water. But I just you know I’m not a lap swimmer these days, but so that’s the story of mine. It’s not the “Oh, I was inspired,” or, “Oh, I had this story building.” It was like, “this is the story they want. Okay, I’ll write it.”

So one of the things as I was saying about our books is there is this sense of community and family really in, in, in each of our books, and I want to know if there are certain ways that you thought about community as you were writing or illustrating, or if it was just something that maybe you weren’t even necessarily so conscious of, but it was just such an integral part of your story that it ended up on on the page. So I’ll start with you this time, Emily.

Emily Joof:

Thank you, Valerie, and thank you for sharing your story.

Valerie Bolling:

Yeah, not my exciting story. But anyway.

Emily Joof:

Yeah. So I think, so the community element in my story came through conversations with others who grew up next to me around me in The Gambia, realizing that so few of us swim. So. So I guess we, that you don’t really think about it when we’re young. But that’s kind, that was kind of the norm. We don’t learn to swim. We go to the beach every week. We never learn the skill, and it might have to do with some of our social, cultural norms. Kind of the, the spirits, we believe, believe, that live in the water or just safety. Our parents don’t want us in there. But I realized I knew maybe a handful of people who knew how to swim, and so it felt like the story needed to be written, not just for my little one, but also for our community to say something big and bold like, we will swim next time.

So the story actually just features the parent and the child. But I had a very strong intention that the book would hopefully connect to my community and by my community as an African diaspora mom, I was very much focusing on my West African community because back in Sweden everyone is half fish. I think as soon as they’re born they, they they go to the water, but also it’s part of the school curriculum. So in grade school there comes a point where there is an actual test, to see whether you can swim from point A to Point B safely, which I think is really brilliant. Because then, children understand that it’s, it’s fun, it’s lovely, but it’s also a life skill, and one that’s really important as you grow up. Yeah.

Valerie Bolling:

Wow! Thank you for sharing that. And how has the book been received in The Gambia?

Emily Joof:

It’s been really, really great just to, to have conversations around the books, because we haven’t, a lot of my peers haven’t thought about the fact that we don’t allow our children to take to swim or teach them to swim, and so, just having the book and them having that conversation or reading, or me reading at story time at schools, has created kind of conscious movements where we now go to the pool because we’re not brave enough to go swim in the ocean. But we now go to the, to th,e to the pool, and we take lessons. So it is a mini movement that’s happening around me, where 4 of us are learning to swim or allowing our little ones to learn to swim, because there’s always, you know, I’m too old. Is my body right for this? Will my hair survive?

Valerie Bolling:

Right? Yeah, that’s a black thing, folks, if you don’t, if you don’t know. That’s yeah, exactly. Wow.

Gee, thank you for sharing all of that, Emily. And what about you, Jack?

Jack Wong:

Thank you, Emily, for sharing all that. That was really interesting. I, what can I say about this from my book? I guess what I would share is also from a creators, side for anyone who who here is a fellow boo, creator, or an aspiring creator, that for me, when I think about community in this book, it’s almost like a solution or something you do with your story, or some, some way in which you convey can be very mundane, and also very deeply meaningful at the same time, and it doesn’t matter which one came first. You kind of arrive at the end, having it all bound up in things that are both decisions made purely out of pragmatics, but also really meaningful.

So what I mean by that is, this book has, as I was saying before, each one was really inspired by just me seeing something out in, in nature. So this is Pebble Beach, and this is…I’m just flipping randomly here. This is seeing kind of dragonflies fly about you as you’re floating in a shallow lake. And so my first mundane, pragmatic problem to solve in this book was it kind of felt like it could be told with just one character experiencing all these things, but I also thought that would kind of be, kind of boring, seeing the same person kinda just go about nature, page after page. So I started thinking about who do I populate these pages with almost as a director or or a casting director who’s casting different characters to play roles in each of these pages.

And with that came this kind of whole snowballing and decisions of who I wanted to include and and how I wanted them to be included who I wanted to give a starring role in this particular page, because I think it connected in some way with the text or with a a cultural element. And so it became a very meaningful exercise to me. And I, I’m certainly inspired by other books to have done this, one of them being the book Love, which is written by Matt de la Pe a, and illustrated by Loren Long, which was really a free verse, poetry kind of book without any characters.

You know, I, I think it was also in the second person, but each page the illustrator Loren Long kind of chooses a different vignette, with different characters to populate it, and I was really inspired by that. So at the end of this whole exercise, I had come up with kind of an organic community that if you read the book through as a reader, and you can imagine them all kind of a stone’s throw from each other. Kind of this organic community has arisen from the text, which, from the, the impetus of it, didn’t really have any sense of character, or who, you know, the, the story is about.

Valerie Bolling:

Wow, thank you for sharing that. Yeah, it’s always so interesting to think about community. And one of the things I noticed is

even the titles of our books. You know we have Emily’s which has first person: I Will Swim Next Time. We have yours, Jack, that says When You Can Wwim, and then Lucy has Our Pool, and mine doesn’t have words like that, but it does say together, which is the sense of community: Together We Swim. And I just think that it’s it’s just an interesting connection between our books. Yeah, Lucy, let’s hear from you.

Lucy Ruth Cummins:

I want to say that Emily’s title is one of my favorite titles, because it’s but I have family in a question. I feel like it’s so kind of interesting or like leaving it kinda open like that feels really like an invitation to pick a book up. I really like that about it for Our Pool. It is a community book, because it’s our particular community. And so it was kind of like a no-brainer that I was just going to kind of work from observation. And the weird thing about being a city person–and I moved to Brooklyn 25 years ago in August–and when I came here, I came from being a person from Central New York, where everybody had a yard, and everybody’s outdoor time was spent somewhat privately, or with the invitation of fence.

And then, when I moved to New York City it was, everybody has an apartment or a smaller space, and then everybody shares community spaces. And it wasn’t something that I had had as an experience as a kid. And then, when I started raising my children in the city, I realized how essential those kind of public works projects are. And it’s like from the playground to the library to the actual parks. We can have a picnic and then swimming pools, which here in the summertime it gets so hot that you would do anything to just get in water. And so I came to really love as a mother, I really started to love what this was. It felt like a luxury thing that we’ve decided is essential, which is so wild to me because it’s like you have to tell people that having fun is important.

And now we know in the United States it’s like a public health crisis that children die from drowning. I saw a statistic today that was like one in 4, that it’s like the leading cause of death among children next to gun violence, which is horrifying. But that people not learning to swim means that there’s a terrible outcome because the danger around water is so serious. And so, having pools and community spaces like that is important because it helps kids survive water. And our pool in particular…I say “our pool”, like I’m saying the title, but our swimming pool. And that’s really how my children refer to it. It’s like we’ve got the biggest swimming pool in the whole world, but it has a zero grade entry, which means, if you’re a little one, it slopes down into the water. Gradually you can sit in an inch of water, or you can stand to your waist. And just even before you can swim, just being able to get close to water. And even when you talk about being at the beach. I know that intensity of waves, and when you’re a little one looking at it means it’s there’s no getting close to it. It’s not inviting. But the the nice thing about saying this community pools important is you can inch into it. You can get comfortable at your own pace. And, and we’re saying it’s important to learn that.

And it’s interesting. When you’re talking about Sweden having like the priority of teaching swimming. It’s a thing that they’ve talked about. The United States is being important because children are dying, and it’s so important. But it was interesting cause my impetus for making the book was to celebrate this thing I loved, and I loved with my family, and I loved in my neighborhood. And then, as you make a book like this. You kind of, your eyes open wider to what the larger themes are, and the larger meaning behind things like public pools. So it was both like an exercise and wanting to draw a lot of different angles on swimming, which Jack destroyed me at everything that he drew in his book I can’t look at–is so much more interesting.

But, but then it became a deeper thing. Where, like I, I feel that urgency now, and I hope that with a book like this it gives you another time to get comfortable with water and the process of getting in water, and maybe that’s one step closer to safety, which is kind of a, I don’t know, it, it feels important in that way.

Valerie Bolling:

Yeah, it’s, it’s definitely important. And there are a couple of things you said that I want to, you know pick up on. One is, you talked about the number of children who die each year, and whatever the numbers are, black, children are 7 and a half times more likely; the, the numbers are 7 and a half times that for for black children, according to the CDC. So it is, it is a public health issue. And then the other thing is access, right? Everyone should have access. And, and you know your public pool, I’m assuming, Lucy, when you go there; is there a fee that you pay?

Lucy Ruth Cummins:

There is 0 fee, and they give a free lunch. I mean, it’s what…those things are like, Wow, you really mean this is important. And I want to say about the free lunch. The free lunch isn’t you have to ask, and you feel sheepish about it. It’s, if you’re a person who appears under 18, you are handed a lunch unless you decline it, which also solves a hunger issue in the summer, when children aren’t at school. I, I get really goose-bumpy talking about it because I, it hits so many angles, what this thing is doing in our neighborhood.

Valerie Bolling:

Wow! Thank you for sharing that. I did, when I asked the question I had a feeling it was free, but the fact that the lunch comes with it, and in the way that you said is just amazing. And so there are so many things, you know, parks and swimming pools and libraries. There are so many free programs. There are so many options for people that, everyone, I believe, should take advantage of and should know about and of course, again, if you know, if we add a little history lesson here, these places were not always open to everyone, and even now sometimes depending upon where you go, certain people may get in, you know, so it, not every place is always welcoming to everyone, but everyone should have access. Everyone should have fun, and particularly during the summer, kids are out of school. They need to be going to libraries to get books, and for summer programming. They need to go to pools. They need to go to parks. So, just so so important. I just want to point out one thing about community in my book, and it really has to do–and if you all are able to PIN me because I really want you to see this up close–this is my amazing illustrator, I don’t own her; Kalani Juanita is an amazing, talented artist, and let me show you what she does for community.

If you look closely and you see who’s in the pool….and I’m trying to see so I can. That’s one. And then on this page…know if I’m holding it so you can see well enough. It’s hard for me to kind of–you know what? Let me take my own advice and see if I can PIN myself, and if that works–no, I just, I’m not seeing it, but I don’t know if you can see it up close. But the idea is that she has people from different backgrounds, people you may not normally see in the water. So it truly is a sense of community and a sense that the pool is for everyone. Can you see this one?

So I just like that to me, says so much about community, and that truly, pools are for everyone, regardless of the type of swimsuit you may wear, or you know, physical challenge that you may have or you know, maybe you’re not skinny, you know, we come in all body types. So I just, I wanted to show that, you know, those pictures as a way of, you know, showing how Kalani built community in, in the pool.

So one of the things I’d also like to ask you about is there’s this, and I was kind of touching on it again earlier when I was talking about access. But there’s still this sort of idea in picture book representation that BIPOC kids belong in urban settings and they are there, and that’s certainly fine. But sometimes people think it’s not usual to see black and brown kids in nature, either camping or biking at the beach, etc, and I’m wondering if either that was something you were thinking about when you were creating your books, or maybe if you weren’t thinking about it at the time. Maybe you just, you know, maybe looking at your books now, or looking at our books collaboratively. Maybe there’s a thought that you have about that, so I’ll start with you, Jack.

Jack Wong:

Yeah, that was certainly something I thought a lot, a lot, a lot about while I was making the book, and I echo what Lucy said earlier when she said that it starts off being a book that you’re writing about one thing and the the number of concerns and and thematics and, and kind of issues that are kind of encompassed by this one activity of swimming, and, and in a public place it it really started to to become more than just about swimming, and I certainly was thinking a lot about it. I was reading a lot of the same statistics that you were bringing up in when I was turned on to the issue of access and disparities in black and brown and other kids of colors learning to swim, and the drowning rates, from that. I was also becoming aware, through making the book, of how swimming, and especially public pools, were arenas of, of the civil rights movement, and how they were kind of grounds for, of conflict, and how there’s a history embedded within it that even as we get to celebrate it. Now there’s there’s an, and while I was writing this book was realizing that this wasn’t a book where I can really speak to all those things at the same time. Nor was it really the right venue for me to just be spitting facts at the reader whether it’s, you know, the the, the age group that I’m writing for, but also because it’s ultimately a book about my experience swimming and the things I wanted to share out of my excitement for finding things in nature.

So I think all of that was, it just fueled the decisions that that I made about the book like I was seeing before it ended up being this book. It, it gave it a tone of being an aspirational book for at least two ways. I mean, one is just the fact that if you’re not someone who can swim and you’re picking up this book is aspirational in the sense that it’s showing that once you can swim, you can go to all these different places and check out all these great sites in nature, and at the same time the book depicts kids of color and also of different body types and disabilities in the water. So it’s aspirational in that way. And I kind of like the fact that they were kind of bound up in one. It’s not very clear that these are two different things, but they’re one in the same that once you learn to swim, this whole world is opened up. And there’s no clear line of when the issue of learning swim begins, and where all those other things are kind of brought into the picture.

And the other thing that I did with the book that was influenced by all the research that I was just talking about was that I still didn’t feel that it was a book where I would share all of those things in a very factual way, but I felt that I should also share my background, and you know the history of swimming through my mother’s generation, my grandmother’s generation, and I just shared the story that way.

Valerie Bolling:

No, that’s wonderful, and I love the back matter in your book as well. So.

Jack Wong:

Thanks.

Valerie Bolling:

Thank you. Emily, what about you? We’re not hearing you right now.

Emily Joof:

To become… Is it there? Can you…

Valerie Bolling:

Yeah. Yes.

Emily Joof:

Okay, awesome. So with this book specifically, the voice, the voice, was, was ours. It was my family’s. And so in the in the images that the lovely Matilda Ruja created for us; she’s a Swedish illustrator who did some really incredible watercolors for us, it felt important that the child represented the voice. And particularly on Swedish bookshelves, back when the book came out. So it came out in Swedish first, and then it came out in English. A couple of years later there was a true vacuum where children of of books that feature, children that look like ours and, like you said, especially children within–it’s not just nature, it’s just children experiencing joy in everyday life. So beyond even kind of certain settings.

So it felt it felt important that the child reflected our voice. So we actually spent a lot of time thinking about the hair! How curly! What would it look like when the child gets in the water? Would it get longer? Does it curl up? Because I felt like this book was going to stand out in in a very significant way in the context of of Sweden, and then, later on, in the world. In, in all my other books that I’ve written we, I do emphasize the importance of inclusion in terms of the bodies that are shown, the abilities. But for this specific book I would say my main thing was that the child represented reality, that they were not staked in, even though some children are… that the mom was a little rounder, but it was okay that she had shorter hair.

I was trying to subtly address some of the stereotypes that were persistent in in our context and it was, It’s a little, it’s a different experience because you’re working with an illustrator. And when I work with someone else on the book, I feel like we’re co-parenting and so I feel it’s important that that they also bring in their words and their perspectives. And what’s important to them, not just how I envisioned it. And, in fact, that’s how the book ended up representing some of the, some of the waters that are in the book are waters that are more familiar to Matilda than me, because she is ethnically white Swedish and whilst the water in the front, that giant ocean,hat’s more me. So it’s a beautiful collaboration where the reader gets to. to hear my voice and see my part of the co-parenting together with Matilda, and yet I feel like we were able to hit the mark in terms of the representation that I felt was really, really important for us to see.

And I would say, I’ll just wrap it up by saying that I became a writer as my tool was my outlet to address a lot of the social justice issues and the racism that we experience. So before those experiences, I never even considered writing. So I’m very intentional with every story that I write because it has a purpose. It’s, it’s not something that sadly, it’s not something that I do just because I enjoy it. If not, I would keep those stories to myself. I feel like they need to go further. They need to be part of our community. Because they serve such an important purpose.

Valerie Bolling:

Wow! Thank you for sharing that. And I love the idea of author, illustrator, when you and I don’t have the gift that Lucy and Jack do, where we can illustrate our own story. So this idea of co-parenting, because we do call it our book baby, right? So this idea of co-parenting is, is a concept that I really like. So thank you for sharing all that and also being intentional. Yes, when you have certain lived experience, experience, and, as you say, writing these books is an act of social justice, right? And so, absolutely.

Lucy, what about you? And I love, you know, Lucy’s got, you know, Lucy may be white, but the kids in the book are–we got lots of black and brown kids, cause that’s who….

Lucy Ruth Cummins:

We got lots of different kids. Yeah, I mean, that’s the that’s the thing about it, like, I kind of thought and I was making the book because I was kind of approaching it from like thinking of it as just like an artist. And thinking, this looks good like this, what I’m seeing is beautiful. And I want to, I want to see if I can represent it. And that’s like, strictly how I’m thinking. But I’m also like I’m filling the pool kind of like a documentary, and it’s like it’s what I’ve seen. And so there are no no real leaps. It’s really like I was describing the process of writing it at one point, and of choosing the pictures and scenes as being like on Sesame Street, where they used to do like little bits of snippets of documentary, and it would just be like, here’s something we can show you from a couple of different angles. And here are a bunch of kids doing the same thing or something like that, and I always loved that as a kid I–always dug in, and maybe it was the contrast between the rest of the show but I wanted my book to kind of feel that way where you will be like: Hey, look! It, here, here we all are, and here. Here’s what we’re up to, but by necessity. It’s just actually who, who’,s who I swim with. And so that’s using the book. But there’s a lot more neon in my book than there is in my real pool, because I like neon. But people are not wearing neon onto the swimming pool anymore. I don’t know why.

Valerie Bolling:

Yes, they do. I remember lots of neon in the eighties. But it’s been so wonderful to hear each of you talk about your book, some of the things you shared I knew, but there were things that I didn’t know. You know we haven’t had, you know, this kind of conversation with each other. So I’m just so glad that we had the opportunity to do that.

I think at this point I’m going to welcome Alex back, because I want to be sure that we have enough time. I haven’t been monitoring the chat, so I don’t know if there are questions there. If there aren’t, I’m sure Alex will have a couple of questions. I know my Alex.

Alex Villasante:

Well, my first comment, my first comment is, neon never actually went out of style. That is false. If you looked in my closet right now you could see a couple of choice pieces. I’m just saying it’s never not a neon day. What a wonderful conversation! We do have a few questions that I want to get to really quick. Well, not really quickly. But I think that we can do that. We, one of the questions was, what age readers are your books for? And how did that influence plot and language.

Valerie Bolling:

Hmm, okay. I’ll actually start, cause I didn’t respond to the last question. I think–and I obviously, I’m going to have my conversation partners jump in–I know that most picture books tend to get an automatic label of 4 to 8. Sometimes it might be 3 to 6 or something like that, but it’s generally that’s if you look our books up. You know you, it’s around that age group. So I don’t know. I think when you’re writing a picture book, you know that you’re writing for young children, and so you keep that in mind with the language that you choose, the words that you choose.

I don’t know that our stories have big plot, I mean, I think you know mine and Emily’s have this plot of learning how to swim, and when are you going to learn how to swim? I mean Lucy’s is, you know, just the enjoyment at the pool, and, and Jack is, you know, when you can swim here, look at, you know, when you can swim. I love it. How it’s all the nature shots, and then at the end, it’s like, here’s the starting point of the pool. But yeah, if you feel free, any of you can jump in and and respond. Maybe just raise…

Lucy Ruth Cummins:

Okay. And I have that…

Valerie Bolling:

Go over each other. Oh, sorr,y go, Lucy. Yep.

Lucy Ruth Cummins:

And my my flap says 4 to 8. But I was just going to say that I don’t instinctually know when I start kind of writing something, like I would want the word choice to be. I wanted to communicate, but I don’t think I ever kind of let it stop me from telling the story I was thinking about. Valerie, how spare yours is, and how, in a way that’s kind of big; like I don’t know. Anyhow, for I guess 4-8 is correct, but I would not have been able to guess that without looking at the text.

Jack Wong:

Oh, and…

Emily Joof:

Yeah. Go ahead.

Jack Wong:

Do you want to go first, Emily?

Emily Joof:

Not enough…

Jack Wong:

Okay. Well, I was just going to say that I’m decidedly a non-expert at age range. I go, I, I’m aware of the same things that Valerie and Lucy you mentioned, which is the age on the flap. But, I often will read a book to one class, so let’s say, grade ones and twos, and I, I guess, flying over their heads is the wrong, wrong way of saying it, but it won’t capture their interest in the same way, and I will feel that it’s kind of like an age mismatch with the vocabulary, and then I would read it to someone who’s 4 years old, but in a different setting.

Maybe it’s, you know, 3 people, a, a, 3 kids at a library in a more intimate setting, and they’d be captivated, and all the experiences I’ve had doing school and library visits just kind of confused the matter more than it has really clarified anything. I, so I really just end up writing whatever I want to write and letting somebody else tell me if I cross any age lines, and even then I’m, I’m a little bit stubborn, because when I was going through the editing process for this book previous to my publishing, I just mean when I was kind of editing it, and showing friends and, and, and mentor,s that kind of thing. There were a couple of words like amphitheater and tannen, soaked, that consistently got noted for being advancef for the age group. And I just said, well, isn’t there that whole thing where, like the the parents read the books to the kids, and the kids don’t know what it is, you just tell them so. I just really liked the word. So I stuck with them, and it ended up making it into the book.

And I’m gonna riff off that and say that one of the comments I got was actually for the end of the book, where it says, one of the the penultimate lines is, “when you can swim, I’ll take you there,” so I’ll take you to all these places and throughout the book, as been when you can swim. I, or we, will do this, or I will take you here, and we will do that. So it ends with “hen you can swim, I’ll take you there.” And I got multiple instances of feedback where, because of this convention in children’s writing, where we focus a lot on a child’s agency to do something on their own, to not having a grownup solve their problem. The, the recommendation for me was to change it to “when you can swim, these are the things you can do when you can swim. We can go together.” to kind of, to kind of turn the agency more towards the child. And I just kept thinking what Kid doesn’t like hearing that their parent, or grownup, or, or whoever is going to take them somewhere, like who doesn’t want to hear: “I’m going to take you to Disneyland. I’m going to take you to them all. I’m going to take you to buy candy.”

So I think I’m, I’m going off on a tangent. But I think it’s was also an indication of age, because at a certain age, let’s say 4 to 8, or 3 to 7, or whatever, I think, enveloping a child in love and care, and, you know, “I’m going to take care of you” is absolutely warranted, and I think, despite amphitheater and tannen, soaked, and all those stupid words I chose, I think the feeling I was trying to convey was for that young audience, of an audience who is at an age where they really respond well to someone telling them, “you know, once you learn to swim, we’re gonna go there together and, and and it’s not just something you go off and do by yourself.”

Alex Villasante:

That’s beautiful, Jack. Thank you for that. Yeah, Emily, did you want to jump in as well? I thought you might have had a comment. There, I don’t want to cut you off where we go to the next question.

Emily Joof:

So Megan.

Alex Villasante:

Can’t completely hear you…sorry.

Emily Joof:

…answer was so perfect. I think I’m happy to leave it there. I’m also a nonconformer.

Jack Wong:

The stories for…

Emily Joof:

Whoever it suits.

Alex Villasante:

While you were talking I was thinking, I don’t write picture books, but I know quite a few teachers who use picture books, picture books to teach creative writing to older kids, to middle school and high school, because it’s it’s really such a wonderful teaching tool on a lot of ways of like structure. And actually, we have a question about structure. Which is: how do you decide on the structure of your books?

Emily, do you want to start since you’re you were last?

Emily Joof:

Sure. Yeah, sure. So with structure, I struggle with structure. I feel like the story tells me the structure. And so when I write, I tend to lay out the idea, the characters, what I see, and then when I’m happy with a certain version of a draft, then I share it with a publisher. Who then says, maybe you need a little more structure? So I think that’s a little difficult for me, because I’m, although I’ve been writing for quite a few years now, and I’ve got a few books. I still often feel like the story’s in the driving seat as opposed to me being in the driving seat. As in the story needs to be told in a certain way. And I learn to shift and, and, and kind of adapt and think about language, and, and think sometimes about age range of readers but I really feel like structure is something a little bit like the age thing where it’s a convention that comes from maybe the publishing side, or, or the way certain stories or the majority of stories have been enjoyed. But I love the unconventional. I love wordless books. I love books that make you hop when you read, and those lack structure in a conventional manner, and perhaps that’s why I struggle with structure. Sorry. That’s not a very helpful answer, but it’s an honest one.

Alex Villasante:

We love that. Yeah. Anybody else want to chime in on scope on a structure?

Valerie Bolling:

I noticed that we’re getting close to time. So if there may be other questions, I don’t think we all have to respond to each of them…

Alex Villasante:

Well, I did want to very quickly read out two comments that you might not have seen, because they’re they’re lovely. From our friend Karol, we have a “thank you” to all panelists for including disabled folks in your discussion of the diversity in your books, and to Jack Wong for using the word disabled. Thank you for that. Thank you, Karol.

And Susanna also said, I appreciate, oh, your comment. “I’m a super beginner.” Welcome, Susannah, writer, and I feel like I tend to feel super-limited when thinking about the age range. So not letting that stop me would be nice for her to hear. So that was wonderful. And I think as we are getting close, maybe we have one more question.

Which would be, this was a an earlier question that was dropped in…

Hair and it, you touch on this a little bit. But maybe it’s more of a comment. “Hair has become a big barrier for us. As the girls get older they don’t want to deal with their hair, or be the only one in the pool with a cap.” So I think that speaks a little bit to what you were saying, Valerie, about black and brown kids being even seen portrayed in, I know, on the cover of your book, Mama’s’ in a cap, and normalizing that, you know, way of being in the pool and still having all, all of the the things that you need. So I think that’s a lovely, a lovely comment as well.

So thank you for that, for that question and I’ll ask our final question. Maybe we can get an answer from everyone before we say good night, is: apart from the word “swimming” or “swim,” in one word, what is your story about? I love these questions cause they make you think, putting you on the spot a little bit. But one word that your book is about.

Lucy Ruth Cummins:

I guess I would say “neighborhoods.”

Alex Villasante:

Yeah, I love that. I stumped you, Valerie. I’m sorry.

Valerie Bolling:

No, no, because I have all these words. I, I have to go with at least two. I you can’t give me…

Alex Villasante:

Rule breaker!

Valerie Bolling:

I have…

Alex Villasante:

The name of the…

Valerie Bolling:

Hey! I led the discussion. I, I organized, and thank you for letting me do it, Alex, and break the rule, so I will say “joy” and “perseverance.”

Alex Villasante:

Those are good. See that you can get away with this, because those are very good words.

Anybody else want to chime in?

Jack Wong:

I’m stumped.

Valerie Bolling:

Yeah, it’s not easy.

Emily Joof:

So I would say, “being brave.” Because for me, being brave is acknowledging the fear and being persistent in your efforts to find coping mechanisms that work for you and yeah. So being brave.

Alex Villasante:

I love that. I love that.

Well, I, I want to thank you all for being here, for kicking off our summertime fun, for sharing your stories, and sharing your beautiful artwork as well. And I just think that we at the Highlights Foundation, we really, we, we our mission, is all about kids and representation for kids and empowering kids to be their best selves. I want to just remind people, if you didn’t already know, that Valerie is gonna be on campus with us this summer at the Black Voices In-Community Retreat. I’m gonna pop a link to that, if anyone is interested in checking that out. And we have a couple of other upcoming on campus. If you haven’t been to the retreat center, as Valerie knows, not only is the food great, but everything else is.

Valerie Bolling:

Everything you don’t want to miss out. If you have..

Emily Joof:

I would do…

Valerie Bolling:

To go. You want to go. Yeah.

Alex Villasante:

And if you have the opportunity to hang out with Valerie…

Valerie Bolling:

Thank you. I would love to hang out with you.

Alex Villasante:

Let’s do it. We also have a a Working Retreat: Lyrical Picture Books and Poetry with us,just some of the loveliest faculty that we have, wonderful people, award-winning authors and illustrators and just awesome faculty. And then in November, I know that’s beyond summer, and I don’t want to think beyond summer, I’ve gotten here to summer. I don’t want to think about; I just found my shorts in the closet. I don’t want to. But, but we do have to think a little bit. We have another Working Retreat: Picture Book Authors and Illustrators in November. That’s with Darcy Pattison and Leslie Helakowski and Sarah Gomez Woolley, our own Sarah. So all our friends. If you have any questions about anything that you’ve seen tonight, any questions about our upcoming events, do reach out. But I just wish you the very best night, and I want to thank you again for joining us and have a lovely evening. Thank you, everybody.